History of Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa National Park

Aboriginal people have lived in the area around Uluṟu and Kata Tjuṯa for at least 30,000 years.

Aṉangu Culture has always existed here. The Central Australian landscape (of which Uluṟu and Kata Tjuṯa are an important part) is believed to have been created at the beginning of time by Ancestral Beings.

Uluṟu and Kata Tjuṯa provide physical evidence of feats performed during the creation period, which are told in the Tjukurpa stories.

Aṉangu are the direct descendants of these beings and are responsible for the protection and appropriate management of these ancestral lands.

Early European explorers

The first non-Aboriginal person to see Kata-Tjuṯa was the explorer Ernest Giles, who spotted the domes while leading a party near Kings Canyon in 1872. Giles named the largest dome Mount Olga, after Queen Olga of Württemberg.

In 1873 another explorer, William Gosse, became the first non-Aboriginal person to see Uluṟu, naming it Ayers Rock after the Chief Secretary of South Australia, Sir Henry Ayers.

The next major expedition to the area was a scientific team in 1894. The party was sent to research the geology, mineral resources, plants, animals and Aboriginal Culture of Central Australia. This expedition produced plenty of valuable information about the area and confirmed that the region was not suitable for farming.

Early tourism

In 1920 Uluṟu and Kata-Tjuṯa were included in the South West Reserve, part of a larger system of reserves set aside as sanctuaries for Aboriginal people.

This meant that few non-Indigenous people visited the area until the 1940s, when Aboriginal reserves in Central Australia were reduced in size to allow mineral exploration. A dirt road to Uluṟu was constructed in 1948, and miners and tourists began to visit Uluṟu, Kata-Tjuṯa and beyond.

The Ayers Rock National Park was declared in 1950, the same year that Alice Springs resident Len Tuit accompanied a party of schoolboys from Sydney’s Knox Grammar on a trip to Uluṟu. Recognising the enormous tourism potential of the rock, Tuit began offering regular tours in 1955, with guests camping in tents and drinking water carted in from Curtin Springs.

Kata Tjuṯa was added to the national park to create the Ayers Rock-Mount Olga National Park in 1958. The first permanent accommodation was constructed the same year, while a new airstrip allowed the first fly-in, fly-out tour groups.

Aṉangu were discouraged from visiting the park during this period, but many continued travelling across homelands to hunt, gather food, visit kin and participate in ceremonies.

In 1964, pastoral subsidies were revoked, which saw many Aṉangu coming to live at Uluṟu. After pressure from tour operators, the government established a settlement at Kaltukatjara (Docker River) to draw Aṉangu away from Uluṟu.

Land rights and handback

In 1966, the Gurindji strike at Wave Hill inspired many Aṉangu to leave pastoral leases and return to Uluṟu.

Over the next decade, Uluṟu’s Traditional Owners lobbied the government for the right to their country, expressing concerns about mining, pastoralism, tourism and the desecration of sacred sites.

The historic Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act came into force in 1976. It recognised Indigenous land rights and set up processes for Indigenous people to win back land and manage resources.

The Central Land Council lodged a successful land rights claim on behalf of Traditional Owners in 1979, but the national park was omitted from the claim as it was no longer crown land and so wasn’t eligible.

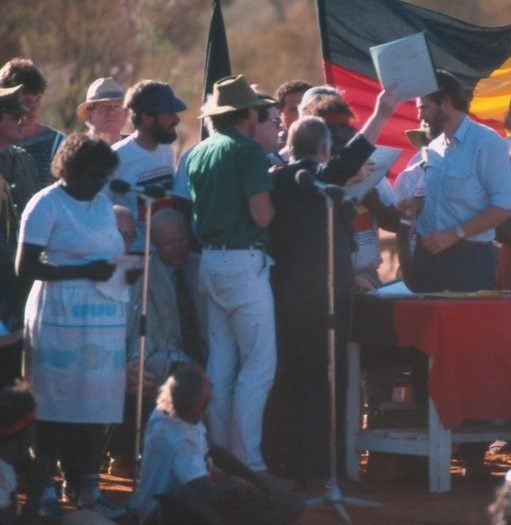

It was another six years before Aṉangu were able to reclaim ownership of the national park. On 26 October 1985, the Governor-General of Australia returned the title deeds to the park to Aṉangu in a handback ceremony on the oval in Muṯitjulu community.

In return, Aṉangu leased the land to the Australian National Parks and Wildlife Service (now Parks Australia) for 99 years. The board of management was set up in December 1985 with a majority of Aṉangu members, and the park continues to be jointly managed by Aṉangu and Parks Australia.

World Heritage listing and beyond

The national park was added to the UNESCO World Heritage List in 1987 for its natural values. In 1994 it was also added to the list for its extraordinary value as a living cultural landscape.

The park’s Cultural Centre opened in 1995 to mark the tenth anniversary of Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa being handed back to its Traditional Owners.

In 2000, the Sydney Olympic torch began its journey on Australian soil with a circuit around the base of Uluṟu.

Throughout the 21st century, Parks Australia has worked with Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa’s Traditional Owners to create better visitor experiences, improve opportunities for Aṉangu and protect the park’s natural and cultural values.

The Indigenous Land Corporation (ILC) purchased Ayers Rock Resort in 2011 and established the National Indigenous Training Academy at Yulara, helping advance the training and employment of Indigenous people in the Australian tourism and hospitality industries.